In the film 100 Days, Director Nick Hughes has offered a psychological close up of the making and carrying out of a genocide. I say, “a” genocide because as we watch the film, we can detect multiple references to the genocide of the Holocaust in WWII, (not to mention Serbia and Darfur) which adds to

the impression that this is not just about what happened in Rwanda, but what happens (and continues to happen) when any group of people systematically murder with the intention of extinguishing another race. Through many close-up shots of various character’s eyes in pivotal scenes throughout the film, Hughes gives the viewer a vicarious and visceral experience of the horror of this hideous episode in African history. One does not have to know that the film begins after the plane carrying the Hutu President of Rwanda was shot down giving the Hutu’s justification for their genocide of the Tutsi’s whom they had lived in “tolerable” peace for some time. This lack of background story or reason for the genocide emphasizes the obvious and important fact that genocide of any race has no justification. As the film opens, the Hutu Prefet is seen entering the office of his subordinate who presides over a village that has been previously shown as peaceful and beautiful with shots of its natural habitat and a young couple in love in the midst of this natural beauty. The Prefet has come to this village to tell this man in charge (or “governor”) that “you have been told–ordered–that the first enemy, before fighting the rebels, are the Tutsi population. We are going to kill them all.” This is Hughes’ first close-up and we witness the determination on the Prefet’s face as he emphatically underlines his point: “That is most important–ALL!”

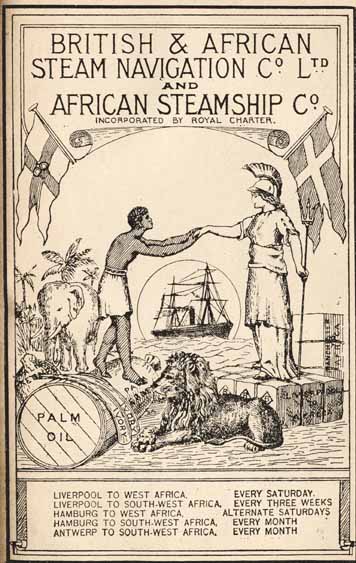

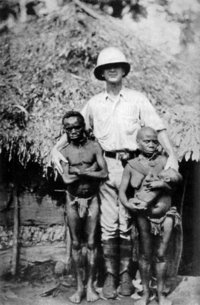

The analogy to the Holocaust is obvious as the next scene cuts to a Catholic priest standing facing the camera giving grace before a meal where the governor who we just saw is sitting with his wife and two children. As the priest prays over the meal, his voice over begins, “In the last war the Germans committed many terrible crimes. Now, the Americans also committed terrible crimes but we don’t remember them because the Americans won.” This scene embodies the Catholic Church’s complicity in this genocide as it condoned the killings. The wife of the governor says, “If the Germans’ killed more people why did they not win? Was God on the side of the Americans?” The priest is quick to point out that God does not take sides, but we know that the Catholic Church certainly does and has controlled much of the Rwandans by its historical education and colonialist ideology. When the governor says, “But Father, I’m being asked to kill,” we are privy to the psychological manipulation of the church as the priest responds: “Killing is wrong. But you are entitled to defend yourself. The Catholic Church is quite clear on this point. God forgives us our sins provided we confess, we repent and we seek forgiveness.” As we see by the end of the movie, this is hypocrisy of the Church’s religious doctrine and manufactured to further the Church’s power. The connection of this scene of the priest, which cuts to the governor’s face at the table then to his face back in his office during the same conversation with the Prefet, further connects the conspiracy between the Catholic Church and this genocide. Another close-up shows the governor sweating then cuts back to another close-up of the Prefet’s mouth talking as the camera pans up to his eyes that have widened with a crazed stare saying, “We are going to clean the whole country. It is your job to tell them that it is up to them to win this war…” The camera lingers on the Prefet’s crazed eyes: “After we are finished there will be no going back to living together because they’ll be no one for us to go back to live with.” What we see as the viewer here is unadulterated, baseless self-righteous hatred and a belief system that has instigated justification for superiority through ruthless power devoid of any human values.

Other scenes with close-ups of eyes continue to lend to the emotional impact of the film as it is through the eyes that many emotions and stories can be seen. The range of shock, intense fear and horror is seen in the close-up shot of the eyes of Batiste’s (who is seen in love with the girl in the beginning of the film) friend who finds Batiste’s family slaughtered in their home. In a following scene, the close-up of the priest’s (who later rapes Josette, Batiste’s virgin girlfriend) closed eyes in prayer suddenly open to look up where the scene cuts to a mural relief of religious figures, indicating the connection to religious mastery of natives and the priest’s later abusive actions of superiority and power. Later we see a close-up of the defeat and fear in Josette’s eyes after speaking to a Belgiun soldier who tells her he cannot take her family with them. Another interesting close-up is the reflection of the Priest in a French soldier’s eye who is describing the two tribes as animals to the Catholic priest who, in turn, describes them as children. These two characters are merely reflections of each other, colluding in the belief that both the Tutsi’s and the Hutu’s are the “other,” cementing their colonialist superiority. And finally, the incredible sadness of the massacre that takes the life of Josette’s father in the close-up of her younger brother’s tear-filled eyes as he witnesses his father being killed before he also is, and in the close-up of Josette’s tear-filled eyes before the priest sends her to witness the massacre in the church.

Other scenes remind us of the Holocaust such as when the governor rounds up the Tutsi boys of the village while he reads off the names of those to be taken into a house and burned. This is reminiscent of the way the Nazi’s called those who were to be burned in the concentration camp ovens. The shaved heads of the young boys are similar to the shaved heads of the Jews. The billowing black smoke rising from the house as it is burning is also analogous to the billowing black smoke of the ovens in the camps like Auschwitz. And in another revealing scene, when a Hutu daughter innocently asks why the Tutsi’s are different than they are, her mother tells her because they are tall, thin, small nose, head shape etc. Basically, their appearance is their only crime, as the Nazi’s believed of the Jews. It is evident that 100 Days tells an important story of a process so insidious and powerful that it effects unspeakable actions of people against others. Ultimately, it is the allure of power that seems to be the motivational force behind the senseless acceptance of a reality that goes against human decency. It is the troubling story of a psychological enigma that is both historical, and, unfortunately, perhaps unstoppable.

March 25, 1998, in Kigali, Rwanda President Clinton apologizes to the victims of genocide...

"... the international community, together with nations in Africa, must bear its share of responsibility for this tragedy, as well. We did not act quickly enough after the killing began. We should not have allowed the refugee camps to become safe havens for the killers. We did not immediately call these crimes by their rightful name: genocide. We cannot change the past. But we can and must do everything in our power to help you build a future without fear, and full of hope ..."

May 7, 1998, in Kigali, Rwanda U.N. Secretary-General, Kofi Annan apologizes to the Parliament of Rwanda...

"... The world must deeply repent this failure. Rwanda's tragedy was the world's tragedy. All of us who cared about Rwanda, all of us who witnessed its suffering, fervently wish that we could have prevented the genocide. Looking back now, we see the signs which then were not recognized. Now we know that what we did was not nearly enough--not enough to save Rwanda from itself, not enough to honor the ideals for which the United Nations exists. We will not deny that, in their greatest hour of need, the world failed the people of Rwanda ..."

(www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline).

“The Canadian Foreign Minister, Bill Graham, told the conference that ten years after the genocide the international community had still not learned how to stop such killings from happening again. ‘We lack the political will to achieve the necessary agreement on how to put in place the type of measures that will prevent a future Rwanda from happening,’" he said (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/3573229.stm).