What greater tragedy is there than the corruption of innocence? This is the tragedy that unfolds in heartbreaking detail in Nigerian director Newton Aduaka’s film Ezra, screened at the 2008 Pan African Film Festival in Los Angeles. Winner of the 2007 Yennenga Award for Best Film at the African Film Festival, FESPACO, Ezra makes an important statement about a growing problem of war, the psychological damage wrought by diminishing armies on the children they kidnap for use as soldiers.

Aduaka, who has at least four other feature films and various shorts to his credit, raises our awareness of what it’s like to be a child of war in Africa. Through a series of flashforwards and flashbacks told by both the protagonist Ezra, and his sister, we get two different perspectives of a horrendous, unavoidable situation and the psychological struggle of countless children in many African warring nations. The film opens with two scenes that cut back and forth between a happy seven-year-old Ezra running to school and the interior of a classroom and teacher writing a lesson on the blackboard portentously entitled “Why I love my country.” Ezra’s sister is at her desk looking out the window for her tardy brother when we see Ezra running towards the school. It is eerily quiet except for the sounds of children beginning their writing exercise. Suddenly, soldiers appear and begin shooting and dragging screaming children, including Ezra, from the school into the bush. The film continues with scenes of indoctrination by adult soldiers as innocence is systematically destroyed. When one little boy asks what they are fighting for the reply is: “Justice. There is no justice in this country, only through the barrel of the gun.” The film is excellent in its realism here as the faces of the children look genuinely fearful and the brainwashing tactics are believable. Ezra’s story begins when he whispers to another boy, “To survive you have to do everything you are told. You have to be a good soldier.”

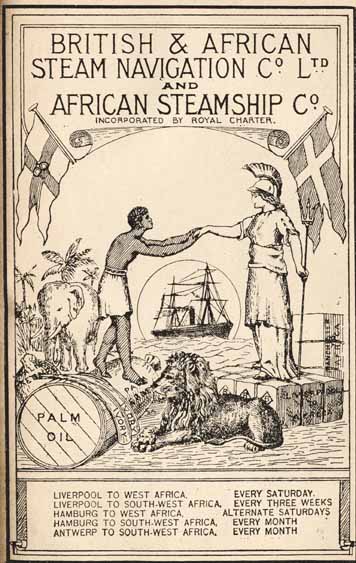

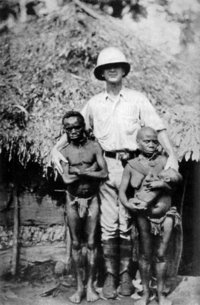

Though non-linear, the film’s story line is, for the most part, fairly easy to follow. Some scenes make more sense later such as when Ezra is standing on top of his own parent’s home that he helps to destroy because we ultimately find out that he is drugged. This becomes clearer towards the latter part of the film in two or three short scenes of white American drug traffickers and British military personnel. The British military are briefly seen providing strategic help to the African government army trying to suppress the rebel army. The Americans are briefly seen selling meth-amphetamines that are given to soldiers to promote aggression and delete any memory of their actions so they are able to continue their violent acts. Both of these scenes, though fleeting, seem to be a reminder that the white man is still running the show and add nuance to what is happening to Ezra. There are many-layered, historical reasons for this situation in Africa, and the film does a good job incorporating responsible parties on all sides without pointing the finger at just one.

Throughout the film, flashforwards show Ezra as a sixteen-year-old living in a facility that helps children heal from their psychological wounds and reintegrate into society. We are also introduced to Ezra’s sister at a hearing of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) set up in 1995 in South Africa by the UN after Apartheid to “reveal and heal” the psychological affects of the atrocities that soldiers committed between 1960 and 1994. Ezra is reunited with his sister when he comes back to his home as an older soldier, and throughout the film she is privy to much of his atrocities. Although she is not kidnapped, Ezra’s sister is another kind of victim of war as she is brutalized by a rebel soldier who cuts out her tongue. She is asked to be witness at Ezra’s TRC hearing revealing things that Ezra cannot remember doing, and this enhances the complexity of their relationship.

In a creative metaphor used by Aduaka for those familiar with Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Africa’s most famous book about the disastrous affects of colonization, we witness the eventual melting of Ezra’s emotional and intellectual wall that he has created to survive. He begins to question the authority of his kidnappers and the real meaning of what he is doing when he admits to identifying with a young boy in the novel who gets sacrificed because of an indigenous African tribe’s unquestioning allegiance to tradition. Ezra is beginning to become aware that he is being sacrificed by his country for diamonds. In such a way, the film seems to reify the idea that war endlessly waged since the colonization of Africa has almost become tradition in the minds of those who have never lived in peace. In the end, the TRC is shown to be quite impotent at restoring a victim’s psychological health from the army’s brainwashing methods and affects of war. A committee member of the Commission says that a soldier “must admit his crime before he can find peace with his ancestors.” Ezra replies, “I don’t remember. I cannot say what you want me to say.”

The interrelations of the main characters are multifaceted and give the film an intellectual depth that is true to its premise. Other than one scene in the army camp of soldiers dancing to reggae music, there is surprisingly little music in the film. Because music touches a deep emotional place, perhaps Aduaka’s film might have benefited from more of it. As it is though, Aduaka does a good job at illustrating, not only the corruption of innocence, but the level of evil perpetrated on children of war that can never be assuaged.

2 comments:

Wow, you write so beautifully, Wendy! No, I'm not complementing you. I'm just being honest.

I am really jealous you got to watch that movie. It sounds intriguing.

It seems rather artistic and profound. The scene where Ezra is dragged away from the school by the soldiers is chilling. It is really tragic, especially since school is a time of innocence and then it is juxtoposed with the violence of war. It's neat that the film is set up in a non-linear fashion. Maybe the director chose to do it that way to mirror the chaos of war. Plus, drugs probably add to that chaos, as well.

I was wondering if the setting was specified, do you remember? Did the director include any hints of where in Africa is the story set?

Di, I think the story was set in Nigeria.

I agree that the film was powerful in its depiction of the realities of warfare. The early scenes where the audience sees the children being inducted to the militia are incredibly disturbing and it's frightening to think that there really are young children in the world who are forced into these lifestyles of violence and corruption.

I see that you enjoyed the non-linear style of the film. I personally found the jumping back and forth to be choppy and distracting, but I did enjoy the juxtaposition of Ezra's version of events regarding his role in the violence that was inflicted upon his former village versus what actually happened.

Post a Comment